The History of Avery Needle Cases

The following narrative was original written in late 2019 and was published in the Feckenham Forester magazine Issue No.7 - 2020.

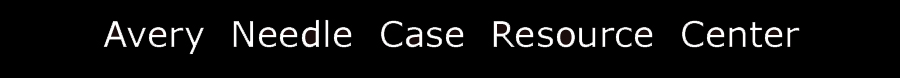

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________For today’s needlework tool collectors, the Redditch area is best known for its elaborately stamped brass needle cases which were produced during the Victorian Period. While these items can be found with over 61 different company names, only one firm dominated the market, W. Avery & Son of Headless Cross. Of the 221 unique designs uncovered to date, only 182 are signed and of these, 124 or 68 percent are stamped with the Avery name. Additionally, of the 196 items where the patent/design registration documents have been found, Avery registered 120 of these designs or 61 percent. No other company even comes close to this. The Birmingham firm Buncher & Haseler registered only 14 designs, the second highest number of Avery style needle cases registered by an individual company.

What makes something an Avery needle case? Not every antique brass box is a needle case and not every needle case in an Avery. At first it seemed obvious that only brass items marked W. Avery & Son should be classified as Averys. However, we now know Mr. Avery frequently made licensing arrangements with other firms allowing them to place their name on his designs. During the time period in which Avery was making needle cases, other companies also patented or registered their own unique needle case designs. Therefore, any small receptacle that meets all three of the criteria listed below is considered an Avery needle case:

1. Made of brass (or rarely gold, silver, nickel or tin),

2. Contains highly complex detailed design that is stamped or engraved onto sheet brass/metal,

3. Identified in some way as a needle and/or pin case made between 1867-1897 in the UK (i.e: information from

patent/design registration documents, journals, advertisements, etc.

from this time period).

All evidence uncovered to date indicates Avery style needle cases were only produced during a short period of time between 1867 and 1890, with a few added around the time of Queen V ictoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. No records have been uncovered so far that give us the details of exactly where and by whom they were manufactured, therefore one must look for historical information in the records that are available. And what are these records? Patents and design registrations, advertisements in books and journals, city and trade directories and company histories. But these only tell part of the story. We need to keep in mind that just because someone registered a design, advertised the sale of a product or had their name placed on an item doesn’t necessarily mean they were the ones who originated the idea. The complete history of Avery needle cases will remain a mystery unless new evidence is discovered. For now, we will assume the companies that registered the designs were the ones who created them.

Our history of Avery style needle cases begins in Birmingham. The Beatrice is the first known needle case made of highly decorated stamped brass and was patented in 1867 by James William Lewis, a Birmingham die-sinker. Two years later in 1869, Lewis registered his second needle case, the Unique, followed in 1870 by the Alexandra. At the time these three needle case designs were registered they were not given names; these were added during the manufacturing process as each name was stamped or engraved onto the brass. The patent drawings and descriptions for these early designs focus mainly on the mechanics of the design rather than the detailed decoration. In an 1871 advertisement, J. W. Lewis was listed as a “goldsmith and jeweler, manufacturer of every description of bright & enameled gold lockets, gilt & plated brooches, lockets, earrings, chains, solitaires, links, &c. patentee and sole manufacturer of the Beatrice, the Alexandra and the Unique needle cases”. This indicates Lewis actually made these needle cases as well as designed them.

The second Avery style needle case designer to appear on the scene was none other than Henry Milward & Sons, a major needle manufacturer from Redditch. Milward used his connections in France when he patented his Fan needle case in early 1868 which included a communication from Theodore Givry of Paris. Not only did Givry apply in the UK for the provisional patent for this design a few months earlier, but he also registered a "porte-aiguille systeme eventail" (needle holder fan system) in France in late 1867. This seems to reinforce the idea that Givry actually was the designer of the Fan. Again, the patent was rather generic, describing the mechanical components of the design rather than specifying how the fan panels were to be decorated. Fan needle cases can be found today with at least six different varieties of brass covers. There is also significant variety in the chromolithographic prints found on the interior panels. We know Milward was in business to sell needles not brass needle cases because he only registered 5 unique designs in total and we are not sure if all of these were actually manufactured. Apparently Milward preferred to work with other needle case designers so he could license their designs and place his needles in them. Milward’s name is found on needle cases registered by both Lewis and Avery.

W. Avery & Son revolutionized the design of needle cases, hence the reason his name is used to refer to all fancy brass needle cases produced during this time period. His early designs were mostly the flat-style, meaning they were thin and rectangular in shape in order to conformed to a packet of needles. In early 1868, only a few days after Milward registered his Fan, and ten months after Lewis registered his Beatrice, Avery registered his first needle case, the Golden Casket. Within the next two years Avery registered two more patents which included many flat-style design drawings. To the best of our knowledge only 6 of these were actually produced, although many slightly different versions of each were in fact manufactured over the years. For example, there are 19 different Quadruple style needle cases, each with identical interior mechanics but different exterior decoration. Many of these appear to have been designed for specific clients. We know Avery licensed some of these designs to other firms, because the word “Licensee” is also stamped on the item, but we don’t know if he was actually involved with the customization or whether the companies created the exterior design themselves. One of these, the Eclectic Needle Case, is Avery’s basic Quadruple model with the Milward name and coat of arms stamped on the exterior. Although it seems unlikely that Avery would have been involved with this customized version since Milward was a major competitor of his in the needle making business, perhaps Avery used these early designs to become better known for his needle cases than his needles. Usually only Avery’s early designs, ones patented before July 1872, have been found with needle manufacturer names other than his own. Milward’s name can be found on at least 6 of Avery’s early needle cases.

Whereas Lewis and Milward only produced a hand full of designs each, Avery would go on to design at least 120 different needle cases. During 1870 and early 1871 he continued to patent/register mostly flat-style designs. Then around the middle of 1871, Avery decided to try his hand at something a bit different, figural needle cases. Because of the restrictive Victorian culture, he knew middle class ladies spent a great deal of their time at home often stitching. Therefore, he decided to create something decorative that would not only appeal to these ladies, but would also be useful, giving them an interesting place to store their needles. This was the perfect time to introduce the fancy brass figural needle case because middle class families, created by the industrial revolution, had more disposable income and could afford to purchase something purely for decorative purposes. One of Avery’s most popular designs from this period is the Butterfly. Avery’s most prolific period for figural needle cases was between 1872 and 1873 when 31 figural needle cases were registered including such interesting ones as the Shield with Rose and the Bird’s Nest Pin Case. From 1870 thru 1873, 12 other firms patented/registered only 20 designs; 6 were Redditch area needle manufacturers who registered 1 or 2 designs each and 6 where Birmingham firms not related to the needle industry. During this same time period Avery registered 47 designs.

Although in successive years the number of designs registered to Avery decreased, we notice Avery entered a new phase; needle cases with Avery’s name stamped on them which were registered by different companies, all from Birmingham. Perhaps Avery never actually manufactured any of the needle cases himself, but rather worked with Birmingham contractors all along. How do we know this? The 1883 floor plan of Avery’s factory in Headless Cross has been preserved and all of the rooms referenced are specific to needle manufacturing. Also, Avery is only listed in Redditch area city and trade directories as a needle and fish hook manufacturer, never as a needle case manufacturer, although needle case manufacturers were represented. We know Avery had a business office in Birmingham from at least 1878 until 1889 where he made pins according to that city’s directory. It seems most likely that Avery always used Birmingham die-sinkers and stampers to create his designs but only later did some of these firms want the designs registered in their names. This seems most probable due to the recent discovery of the Butterfly - Filigree needle case patent, registered to Henry Jenkins of Birmingham in 1869, which is only found with Avery’s or one of Avery's licensee names stamped on the back.

Of the 64 designs created from 1874 through 1880, Avery registered 25, whereas his needle manufacturer competitors only registered 4 designs. Avery’s Cock Robin’s Grave, Wishing Well and Invalid Chair are among his most detailed designs from this period. Another elaborate creation, named the Arts and Industry, was registered by the Redditch needle manufacturer W. Bartleet & Sons in 1878. Four Birmingham companies registered 27 designs during this same time period and most were stamped with Avery’s name. Three were die-sinkers, piercers, stampers and toolmakers: Buncher & Haseler registered 12 designs, Frank Kendrick registered 5 and J. M. Farnol registered 4. The fourth Birmingham company was the gilt jewelry manufacturer Coggins & Baxter who registered 6 designs, the Hygrometer Weather House being the most unique. All of the designs by Buncher, Kendrick and Coggins, with the exception of two, are only found with Avery’s or one of Avery's licensee names stamped on them. How do we know these companies were designing specifically for Avery? Exhibition reports and articles written in the 1870’s, describing the beauty and elegance of Avery’s needle cases mention 19 designs of which 5 were registered to Buncher & Haseler, 1 to Coggins & Baxter and 1 to Farnol. Additionally, the patent photograph for Farnol’s Stile needle case contains Avery’s name and Avery registered several designs during this period including the Lighthouse with Boat using Farnol’s Birmingham address as his own.

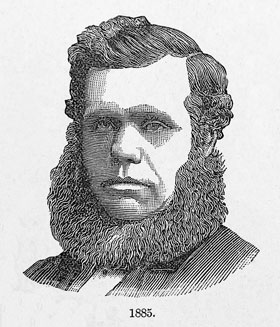

After 1880 brass needle cases must have gone out of style as Avery registered only 5 designs between 1881 and 1890, the most elaborate being the Eiffel Tower which made its debut at the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris. Only 2 other brass needle cases were registered during this time period, both in 1885 by Buncher & Haseler and both were produced only with Avery’s name. The last known Avery style needle cases were made in 1897 for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Two versions were created for this event. A Quadruple with the words “1837-1897 Diamond Jubilee Reigned 60 Years” contains two tiny brass inlaid portraits of the Queen, one from her coronation and another of what she looked like 60 years later. Although the registration document for the second item, known as the Diamond Jubilee - Lap Desk, has not been found, this needle case contains the exact same brass portraits of the Queen.

Terry has been collecting Avery style needle cases for over 27 years. After a few years of research, she wrote her first book about them entitled My Avery Needle Case Collection in 2012 and a second book A Guide to Collecting Avery Needle Cases in 2017. In between researching and writing these books she launched her website The Avery Needle Case Resource Center at www.coulthart.com/avery in 2014. Terry has given lectures on these needle cases in three continents. She is currently working on a third book due for publication next year entitled Histories of the Redditch Area Manufacturers Associated with Avery Needle Cases.

Additional biographically information can be found on her website at www.coulthart.com/avery/aboutus.html. Terry may be contacted by email: meinket@yahoo.com.