My Visit to England in Search of W. Avery & Son

The following narrative was original written in late 2012 and was published in the Spring 2013 issue of the Thimble Collectors International

Bulletin. The published version is a bit smaller than what is presented here because it was edited in order to fit the available

space in the Bulletin. Therefore, the version below contains more information and more photographs than the published

version. It is divided into sections to make it easier for individuals to access the information they are interested

in. The sections are:

Introduction

Headless Cross

Forge Mill Needle Museum, Redditch

D. Leonardt & Co, Highley

Vin Callcut – Copper and Brass Historian, Broseley

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham

Museum of the Jewellery Quarter, Birmingham

Pen Room Museum, Birmingham

Great Hampton Row and Barr Street, Birmingham

Shakespeare’s Birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon

Summary

Footnotes

Introduction

Most of the research for my book “My Avery Needle Case Collection”, published in April 2012, was completed in 2011. In the process I learned about needle making as well as needle case manufacturing. I discovered that pen nib boxes are frequently mistaken for needle cases. An 1883 floor plan for the W. Avery & Son factory as well as an 1885 drawing of Mr. Avery were found. Interesting information about William Avery, his ancestors and descendants was gathered. Along the way several people in England helped with my research. While waiting for my editor to make the final changes before publication, I decided I needed to visit some of these people and the places where my needle cases originated. A previously planned week long vacation to Belgium with a friend was already on my calendar for the fall of 2012. Since we were going to be in Europe and knew another trip wouldn’t be possible for at least a year, we decided to add five extra days to the Belgium trip. This way we could take the Chunnel to England and spend the additional time visiting the Birmingham area.

Prior to the trip, I discovered a lovely three bedroom cottage for rent in the English countryside a few miles west of the town of Alcester. Alcester is located about 30 minutes south of Birmingham, the center of the Industrial Revolution, and 20 minutes south of Redditch, the world’s center for needle production in the 19th century. In addition, Alcester is 20 minutes west of Stratford- upon-Avon and 20 minutes north of the beautiful Cotswold area of England. Because of its great location, I decided this would be the perfect place to call home during our stay in the UK. My book editor, who happened to be my cousin, decided to join us at the cottage from her home in Manchester. After spending a day traveling from Bruges, Belgium to England and another day relaxing in the Cotswold town of Broadway, the next two days were dedicated to Redditch and Birmingham.

Headless Cross

Our first stop was William Avery’s hometown of Headless Cross. Headless Cross is actually a small suburb of Redditch, located on the south side of town. Today Redditch has a population of 84,200. Before the trip, I tracked down an 1887-1890 map of the area (see footnote #1). Back then there were two needle factories in Headless Cross on Birchfield Road. According to the map, one was marked “Needle Factory’ and the other “Phoenix Needle Works”. Earlier research confirmed that Phoenix Needle Works belonged to Thomas Harper, another needle manufacturer in the area. Therefore the one marked “Needle Factory” was the location of W. Avery & Son. I compared the old map to a modern one at Mapquest.com and was able to ascertain exactly where the Avery factory was originally located. I also received a little help from Chris Jackson, a stamp collector I met over the internet, who lived in Headless Cross. Chris assured me that the street named Stonehouse Close was exactly in the center of where the Avery factory once was and that was precisely what the map comparison confirmed. Today, Stonehouse Close is a senior living complex of 38 one and two bedroom bungalows built in 1989. Although nothing remains of the Avery factory, there was something special about standing in the place where the needles for my Avery needle cases were once made.

I also wanted to visit a building in Headless Cross that existed when William Avery lived there; a place that he visited. A few blocks away I found just the right spot. When researching Mr. Avery, I discovered he was a prominent member of the local Wesleyan Methodist Church. Not only did he play the organ at church services for many years, but he also taught Sunday school and frequently attended church conferences. In fact, Mr. Avery helped raise funds for a new church when the original building was destroyed during a gale in 1895. The old Methodist Church was only a few blocks away on Evesham Road. I couldn’t help but be disappointed that it was no longer open to the public. Evidently the church was in need of interior structural repairs to ensure the safety of those who entered. I read about the building before the trip and learned that local church services were no longer held here but were moved to another building up the street. According to my research, this redbrick and stone church was built in 1896. Although I was unable to enter, I was able to stand in the vestibule where William Avery surely passed numerous times on his way in and out of the building. As we walked around the church I noticed four special stones placed on the side near ground level. These contained inscriptions to several prominent residents indicating the plaques were placed there during the building’s construction. What a pleasant surprise to find one was a memorial to Mrs. Wm. Avery who died in June 1895, additional evidence that Mr. Avery was a man of some standing in his community.

Forge Mill Needle Museum, Redditch

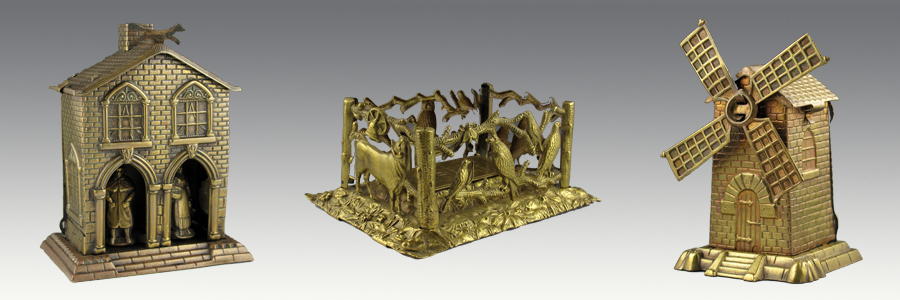

After a quick stop at the Redditch train station to check out the parking situation for the next day’s journey to Birmingham, we headed to the Forge Mill Needle Museum north of the downtown area. The museum, which opened in 1983, preserves the history of the needle and fishing tackle industry during the Victorian Era. During the Industrial Revolution, 90 percent of the world’s needles were made in the Redditch area. The museum complex consisted of two buildings. The Forge Mill was built around 1730 and is the only water powered needle scouring mill in existence today. The three story building next to it, with 1816 inscribed on the front, houses three stories of museum exhibits. The most interesting is the top floor where one sees examples of needle and fish hooks made by a variety of different companies. Several large displays, made for industrial exhibitions in the 19th century, stood out including ones from John English & Son, James Smith & Son and William Hall & Co. It was amazing how hundreds of needles and fish hooks could be arranged in patterns to form such intricate designs.

Also on display in this section of the museum were a variety of hypodermic needles, needle packets and of course needle cases. In one display case there were approximately a dozen cruciform needle cases, each resembling a small square cardboard box when closed with the exterior sides often covered with chromolithography prints. When open the four sides fold out to produce the cruciform shape and four additional interior panels open out to form another cross at a 45 degree angle to the first. The exterior or underside of each panel contained a different print whereas the interior surface was designed to hold a needle packet. Also popular were Mitrailleuse style needle holders. These cylindrical tins contained the name of the company whose needles were within. To release a specific sized needle, all one needed to do was twist the cap to choose the size and then shake the case to discharge the individual needle. However, for me, the most interesting display was the one to W. Avery & Son. Although it was small, with only twelve mostly flat style brass needle cases, it stood out as a memorial to William Avery in a way I never imagined. One of my reasons for visiting the area was to see if some type of memorial to William Avery could be established. I dreamed about changing the street where he lived to William Avery Memorial Highway or Avery Lane (they do this all the time back home in the Chicago area). Or maybe a new gravestone could be erected in his honor at the local cemetery since his original head stone no longer existed. However, now that I was at the needle museum I realized this was the best place for a memorial since the museum was part of the local heritage, an historical building that could never be torn down or replaced.

Prior to our trip I made arrangements to meet with Jo-Ann Gloger, the Keeper of the Collections at the museum. Jo-Ann and I corresponded several times while I was researching my book. As a result, Jo-Ann offered to give us a personal tour of the museum. After guiding us through the three floors of exhibits we exited the main building to see the water wheel in action. The day we visited a group of school children were also touring the facility in order to learn about the heritage of the area in which they lived. Because of their visit the water wheel was in operation that day. A few minutes later we entered the older building of the museum complex which contained models and exhibits demonstrating the steps involved in making a needle during the Victorian period. In one room we saw a pointing machine used to sharpen needles. In another, a kick-press for stamping the heads into the needles and a fly-press to punch through the eyes. For me these machines were fascinating since similar presses were used to make needle cases. What I found most interesting were examples of double-headed needles in one display. The wire used to make a needle was originally cut to the length of two needles to make it easier for workers to handle. Only after the two ends where sharpened, the head pressed in and the eyes punched through were they split to form two individual needles. The one room that would have been the most difficult to recreate elsewhere was the scouring room, located inside the lower level of the building near to the water wheel. Entering this room was as if one returned to the 1800’s.

After a thoroughly enjoyable tour we stopped at Jo-Ann’s office briefly to discuss the history and future of the museum. Jo-Ann gave us each a couple of old needle packets so I would have something to place in my needle cases to always remind me of our visit. Before leaving I came to the conclusion that this would be the perfect home for my needle cases someday. What better way to create a memorial to William Avery then to bequeath my collection to a museum.

D. Leonardt & Co, Highley

As there were two other stops to make before the end of the day we said our goodbyes and settled in for the 40 mile drive to Highley in Shropshire. During my research phase in 2011, I made the acquaintance of Mr. Nick Stockbridge, Chairman and Managing Director of Manuscript Pen Co/D. Leonardt & Co, located in the town of Highley. Nick provided me with most of the detail proving one item that was previously classified as a needle case was in fact a pen nib box. D. Leonardt & Co is one of the only pen nib manufacturers from the Victorian period still in business in the Birmingham area. The firm moved from Birmingham to neighboring Highley in 1949. Although Nick was unable to meet us personally, due to a business commitment in London, he made arrangements for us to visit his pen nib factory so we could see how pen nibs were made. Now you are probably wondering why pen nib production would be of interest to a needle case collector. Actually there are many similarities between needle case making and pen nib making. Each involves a series of steps using sheet metal and a variety of equipment. Seeing how these devices are used to create pen nibs would give one an idea of how these same types of machines could be used to make needle cases. Unfortunately there is no needle case manufacturer or museum to visit so one has to find other ways to learn about the manufacturing processes used in the 19th century.

The drive from Redditch to Highley was quite stressful especially for us Americans. It’s not just the driving on the left side that is confusing, but you always have to be looking in the opposite direction for traffic. In addition, the authorities in the UK have attempted to replace every stop light in the country with a roundabout! The end result is that it takes at least two people to drive. One who actually sits on the right side and drives the car and another to be navigating and constantly issuing commands to watch out for this or that and stay on the left side. Needless to say, it took us twice as long to reach our destination than originally planned. We feel this is positive evidence that the British mile is longer than the American one!

When we arrived at the Manuscript pen factory we met the Operations Director, Linda Jones, and her colleague Penny. After introductions, they took us on a quick tour of the factory. What amazed me was that workers were using the same fly-presses that were used back in the 19th century by D. Leonardt & Co. Not only that but I never would have guessed how many times each nib was inserted into a different press to complete a small part of the manufacturing process The first press cut the nib blank out of a sheet of thin steel, sort of like cutting out a cookie with a cookie cutter. That blank nib was then inserted into a different press that stamped the name of the company on it. It was then inserted into another press that cut a small hole or pierced the tip so it would hold ink. Then the same nib was inserted into yet another press that raised the shape into the nib, giving it a semi-cylindrical form. Lastly the nib was inserted into still another fly-press that cut a small slit in the tip so it could be dipped in ink. These steps were known as blanking, marking, piercing, raising and slitting.

This got me to thinking that perhaps there were a few more steps in the needle case making process than what I originally uncovered and described in my book. I wondered if perhaps needle cases were made in a similar fashion. First a press to cut out the basic shape, a second to cut out additional detail, another to stamp the design and bend it into shape and another to stamp the manufacturers name. I had assumed that one press did all of this but reflecting on the way pen nibs were made, it makes more sense that needle cases were made with at least two or more presses, instead of one. Originally my purpose in visiting Highley was to meet the person who helped me with my research, but I left the town with a new understanding of the stamping process.

Vin Callcut – Copper and Brass Historian, Broseley

From Highley we drove about a half an hour north to Broseley to visit Vin Callcut and his wife Hilary. Vin is a copper and brass historian who was referred to me by Martin Ellis, curator at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Vin is considered to be one of the top historians on the topic in the UK and spent 57 years as a leader in the copper industry. Since brass is an alloy of copper and zinc his expertise is also in this area. I consider Vin to be the one person who provided me with the most assistance while researching and writing my book. Without him I would never have learned all of the things I did and could not have written intelligently about the process and steps needed to create and manufacture brass needle cases in the 19th century.

Although we got lost several times on our journey we finally made it to the street where Vin lived only to find that none of the house numbers followed any kind of order. In the U.S.A. we are spoiled with perfectly square blocks and house numbers in consecutive order, even numbers on one side of the street and odd ones on the other side. However, in Broseley, Church Street started out with something like 2, 3, 6 and then went to 26, 7, 62, 15. After a couple of blocks, just as we were ready to throw in the towel, we looked up to see a woman standing on the curb holding a sign with my name on it. Hilary anticipated that we might have some problems so she decided to wait for us with the sign. We enjoyed a delightful visit with Vin and Hilary which include a delicious dinner. I even got to try my first Scotch egg which was wonderful. After dinner Vin gave us a tour of his house where we viewed his extensive copper collection and the computer room where he hosts the website www.oldcopper.org. Unfortunately we needed to depart an hour and a half after our arrival as the afternoon was coming to a close and we did not want to drive in the dark. Approximately fifty-four roundabouts, three major towns and five minor navigation errors later we arrived at the last major turn of the day where we couldn’t find the road to Worcester. Following three circular loops through the roundabout, I finally figured out the sign marked W’ster was the one to Worcester! After two hours driving, of which 45 minutes were in the dark, we finally arrived back at the cottage where we were able to relax and reflect on all the wonderful things we accomplished in one day. Although it was a whirlwind tour, I felt fortunate that I had the opportunity to do it all.

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham

The next day we drove to the Redditch train station where we left the car. Since we had no desire to drive in a major city we decided to take public transportation for our visit to Birmingham, the second largest city in the UK. The train arrived promptly on schedule and we departed at 9:27am. Thirty-five minutes and ten stops later we arrived at the Birmingham New Station in the center of city where we took a taxi to our first stop, the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. In 2011, I corresponded several times with Martin Ellis, the Curator of Applied Arts. Prior to the trip, Martin recommended we visit the museum’s newest gallery entitled “Birmingham Its People, Its History” which was schedule to open to the public on October 12. However, since we were arriving on October 5 and Martin was not going to be available that day, he arranged for us to meet with Jo Curtis, the Curator of History, who would give us a preview tour. When we arrived at 10:30 a.m. Jo was waiting for us at the museum’s main entrance. She escorted us to the third floor where the history galleries were located.

As we walked through the exhibit, Jo explained the history of Birmingham focusing on the Industrial Revolution since that was the time period in which we were most interested. During that period, Birmingham was best known for its highly skilled and creative workforce - many who worked in small, often self-owned, workshops. In fact at the height of the Industrial Revolution, Birmingham workers and business owners registered over three times more patents than any other city in the UK. I was amazed at how many things were originally mass produced here. These included: guns, horse carriage fittings, steam engines, locomotive and marine engines, railroad carriages, gas fittings, locks, safes, bicycles, weighing scales, papier-mâché, jewelry, steel pen nibs and a variety of buttons made of metal, shell, pearl, horn, bone, wood and glass. Household goods included items such as cutlery, pots and pans, candles sticks, candelabras, metal bedsteads, glass chandeliers and thousands of other practical and decorative items. Birmingham was also considered the toy shop of the world. The toy industry included not just children’s toys but all sorts of other items made of brass, nickel or silver, some of which were plated with silver or nickel since electro-plating was another innovation perfected in the city. One display contained a number of items related to the pen industry including a pen nib box identical to the one I have by D. Leonardt & Co. Wire-drawing was also popular, the end result being used to create needles, pins, fish hooks, wire brushes, hooks and eyes, screws and nails. Although there were no needle cases on display in the history galleries, there were many other objects that were obviously made in a similar fashion; elaborately decorated items that were created by stamping the design onto thin strips of sheet metal. The displays were nicely laid out with several including interactive elements that allowed the visitor to become personally engaged. Our preview tour gave us a new appreciation for the city we were visiting and we were pleasantly surprised when Jo informed us that Birmingham’s sister city in the U.S.A. was our own city of Chicago. Around noon we departed, unfortunately without time to visit the other areas of the museum. Jo did a fabulous job putting together this exhibit and we were honored to be among the first visitors.

Museum of the Jewellery Quarter, Birmingham

Our next destination was the Museum of the Jewellery Quarter which was created to tell the story of Birmingham’s once thriving jewelry and metalworking industry. Located in the old Smith and Pepper jewelry factory building, this museum looks much the way it did when business operations ceased in 1981. However, the tools and manufacturing processes used by the firm have more in common with the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This was especially interesting since the Jewellery Quarter is where the W. Avery & Son shop was located and where their needle cases were made using tools similar to the ones used to make jewelry.

The museum could only be entered with a guide and there were only a handful of people in our group. On one wall of the museum we saw hundreds of dies that were used to make bracelets and pendants. In another room there was a row of fly-presses next to large windows that obviously acted as the main light source in earlier times. Our guide took the time to show us how several of these worked. One press contained the die for a small dog. After inserting a thin strip of sheet brass into the slides on the bottom of the press, the guide pulled the handle. When he released the handle and removed the brass, there were two pieces, the brass sheet with the part of the dog missing and another piece which was a perfect cutout of the dog. The guide then moved over to a second fly-press. This time he inserted a two-inch square piece of thin brass and pulled the handle. However, when he removed the brass, rather than being cutout, it contained a circular impression of a lady’s head in profile in the center of the brass. This was taken to yet another machine where it was inserted and when the handle was pulled, the excess metal around the circular decoration was removed. This was the beginning of an elaborate jewelry pendant. Again, this made me wonder if perhaps needle case making involved more than one press.

Next, the guide sat down at a work bench and demonstrated how several of the old tools were used as well as showed us how to operate a kick-press and burnishing (polishing) machine. Before departing he escorted us to the area where silver-plating took place. Two things he said stood out. First, the antidote for poisoning was kept in a special place in the shop so that all of the workers knew where it was. Many of the metal working processes involved arsenic and other dangerous chemicals and if one was exposed and didn’t know where the antidote was, his or her life could be in jeopardy. Second, unlike workers manufacturing items in brass, the men and women in this jewelry factory were often working with gold. Because of its value, certain precautions were necessary. For example before workers were given their allotment of gold to work with, it was weighed and when they completed their work, the final products were weighed again. This was done to prevent the workers from stealing. Also all of the workbenches were covered with leather aprons to catch any lose gold dust and all of the drains contained filters to ensure no gold was accidently washed away. Although jewelry making is not exactly the same as needle case making, both have many similarities and my visit to this Jewellery Quarter museum probably gave me the best insight into how needle cases were made in the late 1800’s.

Pen Room Museum, Birmingham

After a quick stop at the Rose Villa Tavern in the center of the Jewellery Quarter for a pint of ale and a quick lunch, we headed to the Pen Room Museum. On the way we admired the Chamberlain Clock located in the center of the street in front of the pub. Although modern jewelry shops lined the street as we walked the four blocks to the pen museum, we saw many buildings that harkened back to a bygone era when this area of the city was a booming industrial machine. Nick, Vin and Martin all recommended that I visit the Pen Museum to get a better idea of what a typical 19th century stamp-based manufacturing process was like.

When we arrived we were the only ones in the museum which was laid out in two large rooms, the first displaying all of the tools for making pen nibs and the second containing displays that included items related to the pen industry. Robert Stanyard, the museum’s curator, showed us around and explained the entire pen nib manufacturing process. The highlight was when he allowed me pull the handle on one of the fly-presses so I could create my own nib. I never would have dreamed how easy that would be. I envisioned the fly-press being relatively hard to pull, requiring a certain degree of physical strength. We were surprised to learn that much of this work was originally done by women. Robert showed us the photograph of one woman, Fanny Phillips, who worked for a pen manufacturer for 71 years as a slitter and personally made over 400 million pen nibs. I was also amazed at the variety of nibs and it didn’t take long for me to find my favorite. I still can hardly believe it myself, a pen nib in the shape of the Eiffel Tower! Several displays reminded me of the ones from the previous day - literally thousands of nibs arranged to form unique patterned displays that were taken to international exhibitions where Birmingham manufacturers were highly regarded on the world market. This was important because during the Victorian Era over 75% of all writing in the world was done with pens made in Birmingham. Before departing, we stopped at the gift shop and purchased two items. One was a pen set named “Shakespeare” with a D. Leonardt nib just like the ones we saw them making in Highley the day before. The second souvenir turned out to be my favorite from Birmingham; a thin plastic case that held a small booklet explaining all of the steps necessary to make a pen nib along with a sample nib from each of the steps.

Great Hampton Row and Barr Street, Birmingham

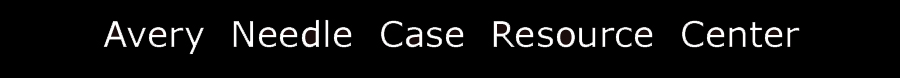

It was starting to get late and we needed to make two quick stops before heading back to the train station for the return to Redditch. We easily hailed a taxi which took us a few blocks away to 192 Great Hampton Row, the address where W. Avery & Son was located in Birmingham. The only business with an address on the street was the Nightingale Knitwear Centre Ltd, at 190, therefore we didn’t know exactly where the Avery shop would have been located. The block was pretty non-descript with four old buildings on the west side of the road and several more modern ones on the east side. Between two of the buildings a gate was open and we could see the interior yard. Surely William Avery walked down this block many times. Perhaps he even walked the two and half blocks to our next destination, 132 Barr Street, to visit a company Avery frequently worked with, Coggins & Baxter. Documents from the 19th century prove that Coggins & Baxter made needle cases at this location, several of which were only produced with the W. Avery & Son trademark indicating they were made specifically for Avery. As our taxi waited we walked to the end of the block to take some photos of the Woodman, a stylish half-timbered tavern that we unfortunately didn’t have time to visit. As I looked up and down the street I felt a warm fuzzy feeling come over me since this was the birthplace of two of my favorite needle cases, the Windmill and the Hygrometer Weather House, both which were patented to Coggins and Baxter in 1873 and 1877 respectively.

A few minutes later the taxi whisked us away and the next thing I remember was being on the train to Redditch. As the train glided along the track and the landscape flashed before me, I couldn’t help but wonder how many times William Avery looked out at the same countryside on his return to Redditch from a busy day in Birmingham. On the outskirts of the city we saw the remains of the canals that were built to provide a way for raw materials and finished products to be transported in and out of the city. Since Birmingham is landlocked, it wasn’t until the canals were dug and the train tracks laid that it became the great city at the center of the Industrial Revolution.

Shakespeare’s Birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon

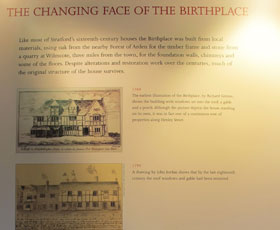

Our last full day in England centered on the town of Stratford-upon-Avon. Although I visited the area twice before in the 1980’s, I was excited to see it again, but not for the reasons most people visit Stratford. The morning was spent at Anne Hathaway’s Cottage and gardens a few miles west of town. Here we saw how William Shakespeare’s wife, the daughter of a well to do farmer, lived before her marriage. After lunch we headed to Shakespeare’s birthplace. William Avery created two needle cases based on this building; however they don’t look much like the building one sees today. I knew from my earlier research that the reason for this was that the birthplace was restored to its original state sometime during the mid-19th century. Unfortunately Shakespeare’s birthplace is one of the most popular tourist attractions in all of England and every day is besieged by hundreds of tourists. As a result it is nearly impossible to photograph the building without a horde of people in front of it.

I was on a mission to find out more about how the building looked before its restoration. Entrance was via guided tour and groups of about twenty people were allowed to enter at regular intervals. Once inside a docent in each of the main rooms shared a little about William Shakespeare and time period in which he lived. About two-thirds of the way through the building I became anxious and asked the docent in the glove shop, who was telling us about William’s father a glove-maker, where I could obtain more information about the history of the building. He informed me that there was one room down the hall that contained a display dedicated to the building’s restoration. Ten minutes later, after navigating our way around several large groups of tourists, we arrived at that room and found that we were the only ones there. Evidently most tourists are more interested in other aspects of Shakespeare’s life. Here we read all about the restoration process and saw original drawings of the building from 1769, 1790, 1807 and 1835. The birthplace was in a rather dilapidated state in 1847 when the government purchased it in order to turn it into a memorial. From 1852-1864 the restoration process began, however it didn’t say exactly when it was finished. At some point the original buildings next to the birthplace were torn down to prevent fires. When William Avery patented his needle case design in 1873, he based it on the building’s appearance from the 1835 drawing. Perhaps that was how he remembered the building from a visit there as a boy, since Stratford was only 17 miles from his home in Headless Cross/Redditch.

Summary

After dinner in Stratford we retired to the cottage for the evening. The next day, Sunday, after one last stop in Headless Cross in honor of William Avery, we drove to London’s Heathrow Airport for our return to Chicago. While waiting for the plane we wandered in the airport looking for something to buy with our last pounds. After purchasing lunch and a few snacks for the plane ride, I couldn’t help but stop at the Swarovski crystal shop next to the restaurant. Wouldn’t you know it, a crystal four-leaf clover, begging me to buy it, was displayed on one of the shelves. As we waited for our flight home, I had time to reflect on all of the things we did and saw in England. Yes, I think I can say I walked in the footsteps of William Avery many times during this trip.

Now that I’m home every time I look at my crystal four-leaf clover I think about what great luck I experienced on this trip. Although I jammed a lot into a few days, I did get to see everything I wanted. And I’m hoping that clover will bring me the additional good luck of being able to return to England someday soon so I can take my time and do it all again!

Footnotes

1 - www.old-maps.co.uk – 1887-1890 pre-WWII 1:10,560 Warwickshire (Redditch) map