|

134th Infantry Regiment Website"All Hell Can't Stop Us" |

|

|

134th Infantry Regiment Website"All Hell Can't Stop Us" |

|

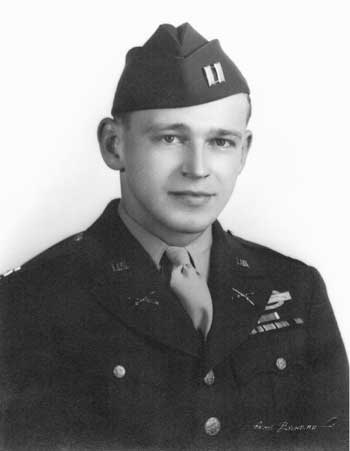

Captain Walter R. Good was a replacement platoon leader, injured by tank fire in Villers-la-Bonne-Eau, Belgium roughly December 30/31st, 1944. He became a POW at that time. A medic named Otto Rauber attended to him until the Germans abandoned Villers around January 10, 1945. Otto Rauber, also with the 137th Infantry Regiment, was not in his platoon but was apparently in the village. He kept moving Capt. Good from building to building because the shelling kept destoying the buildings and barns they were in. With little medical attention, his leg got gangrene and he knew he was dying. After leaving Villers, the Germans took him to one of their field hospitals where they amputated his leg. He was held prisoner in Stalag VI-G, Bonn-Duisdorf, until liberated in late April 1945.

He discussed his experience with his son in some detail after reading the Hugh Cole official history Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge. This inspired him to find Otto Rauber via internet. He did so, and they reunited on Sept 11, 2001 in upstate NY. Otto Rauber was quite surprised to hear from Capt. Good in 2001 because he was "in very bad shape" when they parted around January 10, 1945.

Capt. Walter R. Good was awarded the Combat Infantry Badge, Purple Heart Medal, Bronze Star, American Theater Ribbon, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with one Battle Star (Ardennes) and the World War II Victory Medal. He passed away 2005 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

| A Foot Soldier's Journal - A Story of World War II (excerpt) |

| by Captain Walter R. Good, 35th Infantry Division, 137th Infantry Regiment, Company K |

|

Chapter 7 A Luxury Train Ride Across France We have previously mentioned several moves

by train in the United States and Great Britain.

In all of these, all ranks rode in

passenger coaches, perhaps not the most modern, but nevertheless,

equipment built to carry people.

Not so in France.

The train waiting for us in the station

of Le Harve was made up one hundred percent of freight box cars.

Not box cars as we know them in the

United States.

The European version was, and still is

as far as I know, a much smaller vehicle with only four wheels rigidly

mounted in the frame of the car.

This mode of transportation was not too

much of a surprise, as I had often heard of the French box cars from my

Father-in-Law, and other veterans of the first war. Prominently painted on the side of each car

were the words, 40 Hommes, 8 Cheveaux (40 men, 8 Horses).

It seemed that no one paid much

attention to this notice as each platoon was assigned one car and we had

close to fifty men in a platoon.

To make things worse, my platoon did

not draw a 40 and 8.

We were assigned to a 36 and 6.

Our car had an open platform at one

end.

Things were going to be a bit crowded.

My platoon sergeant and a couple of the

other noncoms asked if they could ride on the platform.

I quickly gave them permission and was

even tempted to join them.

However, I thought I had better stay

inside to help keep squabbling for space to a minimum. After we were all assigned to our cars,

instead of leaving we just sat there for hours.

In due time it was necessary to allow

the men to answer nature's call.

However, I soon found out that many of

them were answering more than one call of nature.

It was soon obvious that a lot of men

were missing so I asked one of those who remained where they were.

His answer surprised me but perhaps it

shouldn't have.

After all we were in France.

It seems that there was a "House of Ill

Repute" quite close to the station.

My informant told me that I really

should at least go and see it.

He said that the men were lined up like

they were going to a movie, he had never seen anything like it.

I decided to take his word for it and

didn't investigate. I don't recall how long we sat in the

station at Le Harve but eventually we did leave, I think with most of

our men, but we really did not have any way to check.

By the time we did leave, it was late

in the day and we traveled most of the night.

We did not travel very fast when we did

move and there were long periods when we just stood still.

At one of these stationary periods, our

platform riders pounded on the door and wanted inside the car.

They were half frozen from the December

weather.

I do not recall exactly how much time

this part of the trip consumed.

It was more than one day as we were

often just sitting on sidings not moving.

One interesting part of this saga

across France is that I have no recollection of who was in charge of our

movements or where they came from.

Although we were nominally still

loosely organized into company level units, it was very loose.

Officers and enlisted men alike were

herded about like cattle.

We were replacements, just one item in

the logistics of supply for the armies at the front.

At the time we probably had a lower

priority than ammunition and rations.

However, although we did not know it at

the time, events were occurring that would change this priority rather

quickly. In time we arrived at a stop where we were

told to unload.

We were moved into some buildings that

looked like they may have been military barracks.

The town was Fontainbleau the summer

home of the French Kings, south of, but not far from Paris.

There were a few French Officers

quartered in the building we were assigned to and we were not too

impressed with them and they were not too interested in us.

However, we were allowed to go into

town that evening so Ken Ploof and I did sample our first French wine.

I did not know it at the time but it

was also my last taste for some time.

As I recall we only spent one night at

this location and the next day we loaded back into our box cars and off

we went. I should note that while we were in Fontainbleau,

we heard our first rumors of something brewing in Belgium and also saw

in an issue of "Stars and Stripes", the army newspaper, that Major Glen

Miller's flight from England to Paris was overdue. The second leg of our trip was much

different than the first.

We seemed to have been given the right

of way and the train made only a few stops during the night and

generally traveled at a relatively good speed.

The next day we found ourselves well

into eastern France in or near the province of Alsace in a town called

Neufchateau.

Again we unloaded and moved into

buildings that looked like old military barracks.

Neufchateau had not been damaged much

by the war and we were able to do some belated Christmas shopping.

A bottle of French perfume did get on

its way to May Hall, although it sure did not get there by Christmas.

At this stop we were able to confirm

that there was something going on in Belgium, but no one seemed to know

exactly what it was.

Some of the rumors were that Germans

had launched an offensive but there was no information just how

extensive it might be.

Whatever was going on, we seemed to be

heading in that direction.

After a short stay in Neufchateau we

switched to truck convoy and headed generally north.

We passed through Nancy and eventually

arrived in Metz. At some point during this leg of the trip,

we got a minor initiation of fire.

It occurred during the late afternoon

at a stop we made for a meal.

It was again at some military type

group of buildings where we were eating.

It was after sundown and quite dark but

no blackout regulations were in effect when we were introduced to "Bed

Check Charlie".

Bed Check Charlie was a remnant of the

once mighty Luftwaffe, the German air force.

What planes they had left they rarely

flew during the day with the overwhelming allied superiority in the air,

so they would fly them at night to do as much damage as possible.

Charlie was a nuisance factor but did

not seem to have much military value.

However on this particular night, the

air raid warning sounded and someone called for the lights to be turned

off.

No one paid any attention to this

order, or request, until either a bomb dropped not too far away or the

anti-aircraft battery nearby started firing.

I'm really not certain which came first

but one or both of them shook the building a bit.

Then the lights went out in a hurry.

Actually during the next few minutes

the answering anti-aircraft fire from the ground seemed to make much

more noise and commotion than Charlie's bombs. Upon arrival at Metz we pulled into what

was obviously an old French Army Post and we soon found that most, if

not all, of the troops being quartered there were from the 35th

Infantry Division, formerly the National Guard of Missouri, Kansas and

Nebraska.

The division was part of Patton's Third

Army.

We were to be assigned to this

division. The group of officers and men that had been

more or less together since England was broken up piecemeal and assigned

to various units of the division.

My job was to be the leader of the

First Platoon, Company K, 137th Infantry Regiment.

My CO was a First Lieutenant named

Travis, I never did learn his first name.

My

friend Ken Ploof was assigned to the 320th Regiment.

I never saw him again and learned that

he was killed in action sometime later. Another officer who had been on the train

with us since we left England was Wilbur Dees.

He had been one of the Tactical

Officers of my class at OCS, Ft. Benning.

I first ran into him again at one of

the stops in England but I was not aware that he was on the same train

as me until he ended up in the same regiment of the 35th.

He was assigned to the first platoon of

I Company.

At that time he had not been promoted

since Benning and was still a 1st Lieutenant.

We will hear more of him later in this

narrative. By the time we arrived in Metz and were

given our Division assignment it was Christmas Eve.

After meeting our regimental and

battalion commanders we were taken to the quarters of our company where

we met Travis, our company commander.

The only experienced platoon leader

left with the company was a Technical Sergeant named Scott, again I do

not remember his first name if I ever knew it.

Scotty had been approved for a

battlefield commission but it had not come through at the time.

However he was given command of the one

platoon in anticipation of the promotion.

As I remember, the other two platoon

leaders were also replacement officers.

I do not remember the name of one of

them, but the other was William McLaughlin.

Bill was several years older than me

but was the only member of the company I saw again after the war was

over.

We corresponded for several years and I

visited him once at his home in Indiana.

Unfortunately he passed away at a

rather early age from causes apparently not related to the war. After we spent some time getting acquainted

as best we could under the circumstances, we learned that there were to

be passes for all ranks to spend the evening in the city of Metz.

Trucks would take the men to the center

city area.

I do not recall whether there was any

limit on the percentage of men who could get the passes.

However we also learned that our

company had a large quantity of mail to be censored.

This chore had to be performed by an

officer and the envelope of every letter had to carry the signature of

an officer before it entered the military postal system.

Since we did not know how long the

division was going to be in Metz all of the new officers of K Company

volunteered to stay in the Barracks and censor the mail so it could get

on its way. When our effort became known, a couple of

the noncoms came to us and asked if they could get us anything while

they were in town.

We said that a bottle of cognac would

be nice for a Christmas Eve treat.

Several hours later the men returned

from the town, these men came into the room where we were still

censoring mail and said, "Gentlemen, here is your bottle of Cognac".

We asked how much money we owed them

and they replied, "We got it for free, the proprietor resisted at first,

but we stuck a 45 under his nose and he gave it to us".

In case there are some real innocents

reading this, a 45 is or was the standard side arm of the military at

that time and for many years before and after that time. Before we go any further, a few comments

about war time censorship might be appropriate.

This was a very time consuming chore

that every officer had to do.

As with many things in the military,

the cast system existed.

Only enlisted men's mail had to be

censored by someone else, officers were allowed to sign their own mail

on the outside of the envelope.

Also as with many other regulations it

was rather ridiculous.

The average enlisted man didn't have

much knowledge that would be of interest to Intelligence agents of the

enemy, and even if they did have tidbits of useful information by the

time it got to the recipient, or was intercepted somewhere along the

way, it would have been out of date information.

However, no matter how useless the job

might be, it had to be done.

I am certain that some officers

probably just signed most of their mail and didn't read it.

This carried a certain amount of risk

to the person doing his or her job since the mail was spot checked at

higher echelon.

This higher echelon, wherever it was,

is were officers mail was also supposed to be randomly censored.

We should note that this censorship

existed only outside of the United States.

This job was not without its

interesting aspect.

It certainly gave one an insight into

the men he had to work with every day.

With some men you could trace their

military career by the addresses of the various women they were writing

to.

Other letters gave one various insights

into the character of the men writing them.

One group of letters I will never

forget were love letters written by a GI to his sweetheart in Brooklyn.

He called her Princess and were really

beautiful letters.

He was also a talented artist and would

illustrate them with sketches of cupids, hearts and other nice little

pictures.

He told me once that his family ran a

restaurant in Brooklyn and invited me to stop around after the war.

Just another thing I should have but

never did do. When overseas a GI could send letters by

the normal mail but delivery was slow and uncertain.

He or she also had the choice of using

V-Mail.

V-Mail was essentially a system where

the original letter, prepared on a specific form was photo copied, the

film then shipped back to the States where a positive print was made and

delivered to the addressee.

This type of mail was given a priority

and delivery was much quicker.

Overseas addresses were the unit

designation and an APO number at some major port city of the U.S. like

New York, APO meaning Army Post Office.

That was to prevent the folks back home

and others from knowing where the unit was located.

The disadvantage to V-Mail was that it

was limited to what one could write on one of the forms.

However you could send as many as you

wanted. I very seldom censored any parts of a

letter.

It usually wasn't necessary.

However, there was one occasion where a

disgruntled GI really blew off steam to someone back home.

He accused everyone from the President

to me of incompetence and many lesser crimes.

In this case I simply took it back to

the man and asked him to reconsider whether he really wanted to send it.

If he did I was obligated to send the

letter, but threatened to censor it until it lost its meaning.

He took the letter back and that was

the end of the episode.

Actually, I don't think I could have

legally done what I threatened to do but he never called my bluff. The bottle of cognac was a pleasant treat

for the balance of Christmas Eve.

We had a lot of help getting rid of it

so no one was in danger of overindulging.

Christmas Day dawned clear and cold if

my memory is correct.

We were given Christmas dinner and I

don't recall much of what we did that day until late in the afternoon

when it was almost dark.

Most of our men attended a Christmas

service in what had probably been an auditorium.

There was a stage at one end and the

Chaplain conducted the service from there.

He wore a white vestment over his field

uniform and I recall that there was a hole in the roof and the moon was

shining through the opening. After the service I was ordered to go to

Battalion headquarters, or it may have been the regimental command post

I'm not sure which.

Whichever it was we were advised that

there was indeed a German offensive in Belgium.

Our mission was going to be the relief

of a "Contingent" of paratroopers that was surrounded in a town called

Bastogne.

I emphasize the word "Contingent" which

in no way indicates that the surrounded troops were a full Division plus

some miscellaneous units.

There was no indication as to how

extensive an offensive we had to deal with. I was given a map of the area where we

would be going and informed that my platoon would be the guide platoon

of the division.

Our regiment would be the right flank

of the division and the Third Army.

Another of the 35th's

regiments was to be on our left and the 4th Armored and 25th

Divisions in that order on the left of the other regiment.

That left one regiment of the 35th

in reserve.

This arrangement meant that our

regiment, and my platoon would be the right flank of the line, and as

far as I knew the whole Third Army.

What we didn't know and I wouldn't

until many years in the future was that the 4th Armored

reached Bastogne the day after Christmas. We were also given some interesting orders.

The first was that when the German army

moved into Belgium at the start of their offensive, all units were

carrying gas masks.

Therefore we would be issued gas masks

before leaving Metz.

Also groups of German soldiers had been

identified wearing American uniforms.

Intelligence information was that they

identified themselves to each other by a scarf, thought to be yellow.

Therefore all personnel were ordered

not to wear scarfs, not a happy thought in the cold weather.

The strangest of all was that we were

to shoot all dogs.

Here the background was that there were

reports that the Germans were turning loose dogs with concealed radios

on them to overhear what was going on among the enemy troops.

The first of these orders did have some

substance as several days later I did see German corpses dressed in

American uniforms.

However they would have fooled no one

at close range as they all seemed to be wearing German field boots,

unlike anything an American GI would be wearing.

However they would have fooled someone

a few hundred yards away.

Fortunately I do not recall coming

across any dogs.

Chapter 8 North to Belgium The exact timing and sequence of events of

the next day or two are a bit foggy in my memory but I do remember the

events quite clearly.

Perhaps I should say this statement

applies to the next several weeks.

As my narrative continues this may be

rather obvious. I do recall that we left Metz by truck

convoy.

I think it was still dark, probably

early in the morning of December 26th, but it may have been

late Christmas night.

We drove north for several hours and

finally arrived at a small village in Luxembourg.

I think the name of the village was

Piero or something like that but I have never been able to find it on a

map. We set up our company command post in a

room of a private home we had commandeered.

My platoon was assigned to outpost the

town, so I assume that we were near where the action was.

Each outpost was made up of four or

five men, with some type of automatic weapon.

I personally took two of the groups to

their assigned locations and one of the noncoms took the rest.

It was not very long before we

discovered that one of our outposts was alongside of a 155mm artillery

battery.

I don't know if anyone knew they were

there but I had been given no indication that other units were in the

area.

I never had time to unscramble that

situation because as soon as I had something to eat, I had to worry

about getting my men relieved so they would not be out there all night

without rations.

I had neglected, forgotten or simply

didn't have enough common sense to give the outpost personnel one

important instruction.

That was to set up a time for radio

contact or any rules for radio communication.

Each outpost had a small hand held

radio.

However in those days battery life was

rather short for electronic devices so they could not be left on all the

time.

It was therefore necessary to have a

timed sequence when each post should check in with the company CP.

With no specific instructions regarding

the radios, our outposts didn't make any attempt to routinely check in

with the CP and we could not contact them.

Again I was fortunate, this oversight

caused no serious problem. We were soon back in our trucks but we did

not go much further and soon were unloaded and started moving as

Infantry was intended to move, on foot.

Shortly after leaving the trucks, we

approached a small river or stream where the only way to cross was a

pontoon bridge.

The only problem was that it was under

intermittent artillery fire.

Therefore we had to run across the

bridge more or less one at a time.

In that way if a shell came close,

casualties would be small.

That is unless the shell arrived at the

time you were on the bridge.

Then the casualty would be more

significant.

However we all cleared that minor

roadblock without any serious complications. A short time later, our column was

scattered by what appeared to be mortar fire.

It took some time to get reorganized

after that and eventually we approached a wooded area where we deployed

into rough skirmish lines as we entered this area. I should note here that our company

commanders had been ordered by higher command to stay in the rear so

most of the green platoon leaders were more or less running the show.

I cannot speak for the rest of them but

in spite of my good background in individual Infantry soldier skills, I

had never actually led a platoon in field maneuvers.

This was real on-the-job training.

I also doubt if any of the replacement

enlisted men had any more training that what we gave at Camp Fannin or

in England.

It was a case of the blind leading the

blind.

I was envious many years later when I

read of units actually rehearsing their maneuvers before the start of

the desert war with Iraq. We had entered the wooded area we mentioned

above when Wilbur Dees' company came to a clearing.

At the time he was leading the company

and he did the same thing I would have done.

Rather than move into the open and

cross the clearing, he started to move around the edge of the woods.

This of course slowed things down and

before he got very far with this move, his company commander came up and

really gave him hell for not striking out right across the clearing.

It is ironic that this company

commander was the first casualty among the officers and Wilbur rather

quickly inherited the company.

I met Wilber briefly after the war and

he had survived with only minor wounds and got his Captain's "Railroad

Tracks", the double silver bars. We did not move very far into the forest

after that event as we were soon ordered to dig in and prepare to spend

the night.

Our bedrolls were delivered to the

area, so we had blankets.

However, the chore of digging a slit

trench in the frozen ground was rather formidable.

However we eventually did finish a

joint project and had a trench deep enough to get us below ground level.

One of the sergeants, the platoon

messenger and I shared the trench and blankets.

The next morning we counted our covers.

There were something like twelve or

fourteen under us and seven or eight on top of us. The terrain we moved into the next day was

mostly wooded.

At this point we were truly the guide

platoon of the division.

I had been given a compass azimuth and

an overlay for the map I was carrying.

The overlay showed a series of phase

lines.

A phase line is where you hold up,

regroup and advise higher authority before continuing.

An overlay is nothing but a piece of

tissue that has been traced from anther copy of the same map you are

using.

So that the recipient can place the

overlay on the same section of the map, the tissue is keyed to the

recipient's map by the rectangular grid lines that divide all military

maps into 1000 yard squares. For some strange reason I remember clearly

that our course was only a degree or two off due North.

All went well that day although

movement by compass course through a wooded area is rather slow.

As we advanced, we found no evidence of

the enemy.

Finally we reached the last phase line

on our overlay.

I verified our position as well as I

could in the woods, sent a messenger to the rear and ordered everyone to

dig in while we waited for orders. Whenever you stopped for more than a few

minutes, it was standard procedure to start digging.

Also I did not have to wait very long

for orders because soon some unhappy Company Commanders converged on me.

They claimed that I was far off course

and pointed to a hill on the map a long way from where I thought I was.

Of course I debated the point and to

find out where we were for certain, radio contact was made with an

artillery spotter airplane flying above.

These planes were small "Cub" civilian

aircraft which were very good for this type of military use because of

their slow speed and ease of handling.

Remember this was in the days before

helicopters.

We put out colored identification

panels so we could be spotted easily and allow the artillerymen to radio

our coordinates to us.

Fortunately, while neither the Company

Commanders or I was exactly correct, I was a lot closer to where we

should be than they thought we were. After this episode we moved on and passed

through one or two small farming villages and as we moved out of one

patch of trees into a cleared area our forward elements came under

machine gun fire from another patch of woods on the other side of the

field.

The terrain we were moving through was

rolling countryside, much like portions of Lancaster County, the Lehigh

Valley or North Central Pennsylvania.

The open areas appeared to be farm

meadows or fields for crops so most of them where of good size, not an

area one would move into if you knew that there are enemy machine guns

on the other side.

Therefore we moved our men up to the

edge of the wooded area and started to dig in again.

As we were taking this position I heard

some rifle fire coming from some of our men off to my right.

I moved down the line to where the men

were firing to determine what they were shooting at.

I could see nothing.

When I inquired they pointed out

several men out in front of our position.

The rolling terrain had hidden them

from my view at my original position.

I'm sorry to report that a couple of

these men were wounded.

However they were quickly evacuated by

a couple of medics.

I don't think there were any fatalities

but I am not certain of this.

One can see that casualties from

"Friendly Fire" is not a new phenomenon. A short time after this unfortunate event,

I was told to report to the Battalion Command Post in a village more or

less a mile to the rear of our location.

Taking one man with me I headed for the

CP.

As we entered the village, we had to

duck under a parked tank when some artillery came in but no harm was

done. Before commenting on the attack order I was

to receive at the CP, one should have a picture of my attire.

Everything I was wearing was standard

army issue including the overcoat.

The only indication of rank was a small

silver bar painted on the front of my steel helmet and a vertical white

strip on the back.

We called this strip our "aiming

stake".

Non-commissioned officers had a

horizontal strip as I recall and a small rank insignia on the front.

We had all taken dirt or whatever we

could find and smeared it over the strips on the back to make it less

prominent.

The insignia on the front of the helmet

was small and not too visible from a distance.

No one was wearing a back pack but I

was still wearing the harness of mine.

Our packs, or Musette Bags were smaller

than those of the men and clipped to a harness at two rings located at

the front of each shoulder.

Whenever the bag was removed as it

always was in an active area, some individuals chose to hang a grenade

on one or both of the rings at the shoulder.

At the time I am describing, I was

carrying one grenade in this manner.

This technique later became the

trademark of General Matthew Ridgeway during the Korean War. One other comment before returning to the

CP, the reader will recall that I had noted that Gas Masks were issued

before we left Metz.

A quick check of our men after just one

or two days in the field showed that I was about the only one who still

had one.

Had the Germans used any kind of gas

the results would have been disastrous. Meanwhile back at the Command Post, the

Battalion staff was briefing me about the attack plan.

There was to be an artillery barrage

first, high explosive mixed with white phosphors.

This was a potent and effective type of

artillery against dug in troops.

Phosphors shells would burst with a

mushroom like pattern and fall into the fox holes or slit trenches.

A piece of burning phosphors landing

anywhere on a person is quite likely to make him get out of his hole

where high explosive shells can put him out of action.

The chemical shells were normally

delivered by 4.2 inch mortars handled by special units. After the timed artillery barrage, the

Infantry was to move forward.

Part of the reserve battalion was to

move up on our right and would be supported by tanks.

I don't know what unit they were from

but the main effort would be in this area.

At one point, I was leaning over a

table where a couple of staff officers were giving me this information

when the grenade I had hanging on my harness slipped out of its ring,

bounced on the table and rolled across the floor.

This caused some momentary panic, but

there was really not too much to worry about.

It took a fairly strong pull to remove

the safety pin from a grenade.

However I wouldn't recommend that one

bounce a grenade off the dining room table. Timing was important to this plan, so by

the time the briefing was finished, the clock was creeping toward the

time when the barrage was to start.

However there was one more snag.

When I came into the CP, which was a

farmhouse in the village, I had taken off my gloves and laid them on a

table.

When I went to leave, I could not find

them.

They were nowhere to be seen.

The Battalion commander, probably a Lt.

Colonel but I'm not certain, was getting itchy and said I would have to

leave without them.

I let him know that there was no way I

was going back to my unit without gloves.

I suppose he decided that he would

rather have a 1st Lieutenant with his forward unit than a 1st

Lieutenant under arrest for insubordination so he just said, rather

firmly, "Someone get this man some gloves so he can go back to his

unit".

Gloves quickly appeared from somewhere

and they fit.

Perhaps they were mine returning home. After I returned and briefed the other

platoons on the plan, the barrage came off as scheduled, we moved into

the open field.

There was no resistance in our area, we

crossed the field into the wooded area on the other side.

We found some abandoned slit trenches

and what looked like a makeshift machine gun emplacement on the edge of

the woods.

They looked like they had been

abandoned in a hurry as there were still some items of equipment in a

couple of them.

We moved through this grove of trees

and pulled up of the far side where we overlooked another small farming

village.

My map indicated that it was

Villers-la-Bonne Eau, The Village of Good Water. There is one part of this minor skirmish

that is not clear in my memory.

I am not certain whether we had armor

support as I described above or if the tanks were brought into action

immediately after we came under fire.

I do remember that at one point in

time, units of one of our other regiments, located to our right, tried

to advance supported by several Sherman Tanks.

This attempt was a disaster, the Tanks

were knocked out quickly and nothing was accomplished.

Whatever the timing of the armor's

demise the fact that they were knocked out quickly indicated that the

Germans had some rather potent equipment in that area.

It probably took one or more of the

famous German 88mm guns to put a couple of Sherman Tanks out of action

so quickly.

If they were indeed 88's, they were

probably mounted on tanks of a panzer unit.

In a couple of days we would know for

certain. We were now overlooking the village we

named above.

As we dug in and prepared to stay

awhile, our company commander ordered a patrol to move forward and scout

out the village.

They did not get very far and were

promptly driven back with some casualties.

The patrol had been led by Sergeant

Scott who I have previously mentioned and who was very fortunate to

survive.

After that we were instructed to dig in

for the night and hot food would soon be sent up.

We finally did get the cooked food but

it wasn't very hot. Since Christmas day we had been living

primarily on K rations with a D ration thrown in sometimes.

The K ration was a World War II

development.

They came in a box about the size of a

cartoon of cigarettes and would fit easily into a field jacket pocket.

Each morning you could pick up three

boxes.

There were three varieties, breakfast,

lunch and dinner.

The main course was contained in a can

about the size of a normal can of tuna or salmon.

Breakfast was a can of bacon and eggs,

lunch a can of cheese and bacon and dinner one of two or three

varieties.

Either beans and ham, or a couple of

other unidentifiable meat based concoctions.

In addition to the main course, each

ration had biscuits, a powder to make a drink and other goodies.

Not the same in the various meals.

For instance it was essential to get a

breakfast ration as it was the only one that had toilet paper.

However in the field it normally was

not necessary to have this item every day.

The reason should be obvious.

Breakfast had a powdered citrus drink

and one of the other meals a packet of Nescafe.

About the only instant coffee available

in those days.

I don't remember what drink was

included in the other meal.

However each meal did have a packet of

four cigarettes.

I wonder if they are included in

today's field rations, I doubt it. These rations would keep you going, I guess

for an indefinite period of time but they sure got monotonous in a

hurry.

The last one I recall eating about the

time we are discussing I took about two bites of the cheese from the

lunch variety and then threw it as far away as I could.

A lot of men would not drink the coffee

and I made it known that I would like to have any they planned to throw

away.

Therefore I usually had a surplus of

Nescafe in my pocket.

The meals were double wrapped.

The outside layer was paper board

similar to a cigarette carton, but the inside wrap was a much heavier

paper board impregnated with paraffin so that it was waterproof and

humidity resistant.

An added characteristic, that I am sure

was not designed but dumb luck, was that this box would burn with a

smokeless flame and would heat a canteen cup full of water for making

Nescafe.

This wasn't taught at Fort Benning but

was one of the first things that one learned from the more experienced

men. That night I don't recall that we did

anything of significance.

Another patrol was sent out from one of

the other companies but I never heard that they learned much.

At one time during the night, we

watched as Germans came out of the village with a tank and chopped some

wood a few hundred yards in front of us.

I am sure that the reader has seen

enough pictures of the Battle of the Bulge to know that the ground was

snow covered, but it was also moonlit so visibility at night was good.

The reader may ask why didn't we fire

on them.

There are two reasons, one, we did not

wish to get tangled up with a tank as we did not have any decent defense

against one easily available.

Two we did not want to give our

position away, they didn't seem to know we were there on the edge of the

woods. I do not recall getting much, if any, sleep

that night.

In fact, lack of sleep is the one thing

that remains foremost in my memory about the time since we left Metz.

Except for the one night I have

described earlier when we had our bedrolls, I really do not recall

sleeping any night.

After the company settled down for a

night there was always something else to do, if it was only finding out

what we were supposed to do next. Much of what happened the next day or two I

probably did not know, but also some of it has probably fogged by the

years.

However to the best of my recollection,

by this time the company commanders were making themselves more

prominent and were more active in the direct control of what was

happening in the forward units.

There was much discussion as to what we

do now.

For the first few hours of the next day

there was no sign of activity in the village.

Had the Germans evacuated during the

early morning hours?

Had they left only a token delaying

force and withdrawn the panzers?

We really didn't know.

I do recall that there was an order for

our company, and I guess the units on our left, to move off to the

north, skirting around the east side of the village.

Travis, our CO, got into a violent

argument with Battalion officers on this point.

So much so that he was relieved of

command.

I never saw him again and have no idea

what happed to him. However, Travis must have made some points

in his disagreement because we were told to send a patrol into the

village.

Sgt. Scott was to lead the patrol, and

for some stupid reason I decided to go along.

So off we went about six men.

We made the edge of the village without

incident, cleared the first house we came to and moved into it.

While some of the men stayed in the

house and contacted higher headquarters for instructions, I took two of

the men and moved around the edge of the village to the next house,

which was downhill from where we were, across an open field but on the

edge of a wooded area.

We inspected this building and found it

empty except for two dead civilians, and old man and woman, apparently

the farmers who lived there.

However the house had windows and/or

doors on only one side and this was the side toward the open field.

There was no way to observe any

activity on the other three sides, especially the side up against the

woods.

Therefore I decided that I did not want

to stay there and returned to the first house.

By the time we arrived, there was quite

a few more men there.

I have no idea where they came from or

who sent them but it looked like we planned to stay awhile.

Among them was a forward observer for

artillery, our new company commander and a number of others with some

automatic weapons and a bazooka or two. A Bazooka was our first hand held rocket

type weapon.

It looked like a stove pipe with hands

grips attached to it.

The name came from a comedian of the

era, Bob Burns, who played a crude musical instrument that looked

somewhat like the description of the weapon I gave above.

The Bazooka was supposed to be an

Anti-Tank weapon.

It had virtually no recoil when firing

what was essentially a small self-propelling rocket type projectile.

The head of the projectile had a shaped

charge that fired on impact from some kind of inertia firing mechanism.

The only problem was that it usually

didn't fire when it hit a curved or slanted surface.

Of course there were a lot of curved

and slanted surfaces on a Tank, especially on the front.

Another disadvantage was that when it

fired it spewed a sheet of flame out the back of its barrel and your

position was easy for the other guy to spot. Our new company commander was apparently

from the Battalion staff and I never got to know his name.

Nothing he did, if he did anything, had

any impact on what happened next. So we settled in for the rest of that day

and that night.

Why we didn't try to move further into

the village or else get out of there, I do not know.

We did know that if there were still

Germans in the area and they wanted the ground we were on, they would

counterattack at dawn.

This was the way they fought.

If they lost a position in a tight

situation, they would almost always counterattack as soon as possible.

This time was no exception because at

dawn, our building came under attack from Infantry supported by tanks,

about four of them as I remember.

I really don't know exactly which

panzers these were but I have always called them Tigers which was the

biggest tank of a Panzer Division.

Whatever they were, they looked awfully

big to me and as far as I am concerned, they were Tigers.

Tigers were basically a platform from

the German 88mm rifle, the best and most versatile artillery weapon of

the war. We were supposed to have anti-tank weapons

deployed up the hill from where we were, but they were 57mm rifles.

A rifle in artillery terminology is a

flat trajectory weapon as opposed to a Howitzer and/or Mortar which is a

high angle fire weapon.

Artillery rifles are characterized by

long barrels, while the barrel on a high angle fire weapon is much

shorter.

Getting back to the 57mm.

This is a British weapon, alleged to

have been very effective in North Africa.

However its problem was that when it

fired, it produced a large sheet of flame and smoke that could be seen

for miles and it was only a matter of time until it drew counterbattery

fire.

It was not easy to move quickly and

could not be manhandled except for very short distances.

For these reasons it was alleged that

the standard operating procedure for 57mm crews was to fire one round

and get the hell out of where they were as quickly as possible.

If they couldn't tow the gun with its

truck, they would pull the firing pin and leave it. As the attack developed, I was on the main

floor of the house but soon found that I didn't have much company.

Also I am not too certain as to the

exact sequence of the events I am about to relate, nor am I certain just

how long a time span was involved.

However there was some exchange of

fire.

At one point, I saw a rifle grenade hit

the turret of one tank.

When hit, the tank stopped, the hatch

opened and someone started to crawl out.

I had a clear view of this and somehow

I got my hands on a Browning Automatic Rifle, really a light machine gun

but with only a small magazine of 20 rounds.

It was a holdover from the First World

War.

I don't remember whether I grabbed this

from another GI or whether it was laying on the floor.

However I got it, I leveled the weapon

at the tank crewman coming through the hatch and fired several bursts

until the magazine was empty.

The man immediately ducked back into

the hatch, I don't know whether he was hit or just reacting.

After he was out of sight the tank

backed down the hill.

I think it returned sometime later. Either before or after the BAR incident, I

recall seeing a bazooka laying on the floor.

I picked it up and examined it only to

find that it had features that I had never seen at Ft. Benning.

I recall that Sgt. Scott was present

and I asked him if he could fire it.

He said yes so I said that I would load

it for him.

These weapons required two men to fire,

one to load and one to aim and fire.

After I loaded a round, Scotty fired at

one of the tanks and he told me the projectile just bounced off without

exploding.

The tank immediately returned fire and

it seemed that the whole ceiling of the house fell on us.

However it may have been part of the

wall, I really don't know.

Whatever, I recall looking around the

room and seeing the tank projectile laying on the floor within a couple

of feet of me.

It had either been an armor piercing

round or a dud.

I didn't examine it to find out.

I do recall that Scotty left after that

incident and I don't recall ever seeing him again. After these incidents, I soon found myself

virtually alone on the first floor of the house, at least in the area I

was in.

I believe there was a second floor and

I don't know if anyone was up there or not.

By this time I had no idea how many

people were in the building.

The Germans apparently knew they had us

under control and they just sat there with a tank on each side of the

house.

I was watching them through the front

door which was in a hallway that led from back to front, when the gun of

the tank I was observing traversed around and was pointing in my

direction.

As I realized that I was looking down

the barrel of a rather large gun, I dove to my left as far as I could to

get into a prone position.

I no sooner hit the floor when I felt

something kick me in the hip.

That was the only sensation of pain

that I had, but I knew that I had been hit.

My first thought was that now I could

get out of this mess, but it didn't take long to realize that this may

not happen.

There was no sense in calling for a

medic so I crawled down the hall and found steps to the cellar and

managed to get down the steps. When I got down the steps, I was surprised

to find quite a few people.

I have no idea how many, or who they

were.

I think at least one of them was an

officer, probably my new company commander.

Several of the men were wounded and

there was a medic who put some bandages on my right leg.

After a while I heard someone from the

first floor calling down the steps to the unknown officer.

He was telling him that he should come

upstairs and evaluate the situation as it looked very bad.

He was suggesting that we should

consider surrendering.

Whoever this officer was, he refused to

move from the basement and kept asking the individual upstairs to

describe the situation to him.

After some exchange along these lines I

finally joined in the exchange and told the reluctant one in the cellar

that if he wasn't going to do anything, we may as well surrender.

So I called to the GI upstairs that he

should signal our surrender.

This was finally done but I have no

idea whether the unknown soldier on the first floor was listening to me

or just gave up on the other officer in the basement and did it on his

own.

However before making the final gesture

of surrender, he gave an opportunity for any who desired a chance to

escape from the house.

I recall one or two men did try but

were mowed down with machine gun fire rather quickly. After the surrender emblem was shown, in a

few minutes we heard several people enter the building.

As someone came to the head of the

cellar stairs someone, I think the medic, loudly called out that the

wounded were in the cellar.

I heard this declaration being

acknowledged.

Sometime after that I was aware of a

German Officer leaning over me and telling me, "For you the war is

over".

He searched me and took the map I have

previously referred to and still had in my pocket.

He interrogated me a little but other

than my name rank and serial number I went by the book and refused to

answer any other questions.

When I did that he proceeded to give me

the answers to all the questions he just asked.

They were not earth shaking items of

intelligence, but did involve our unit designation, when did I arrive in

Europe and a couple of other similar points.

He had obviously got this information

from other men they had just questioned. Thus ended my short and inglorious active

military career.

We had been told at Fort Benning that

any major battle of a war was nothing but a series of little battles and

whoever won most of them, won the big battle.

Unfortunately I was involved with one

of the losing little battles.

None of us had performed very well

although we didn't seem to get much support from other troops in the

area.

Once we got in the house at the edge of

the village, I do not recall ever getting any specific orders as to what

to do or what was expected of us.

Obviously someone else was directing

the effort, whatever it was.

I have often wondered whether I should

have assumed more initiative.

I wish I had enough sense to get out of

that place shortly after we got there.

It was a stupid place to be, especially

if the German Tanks were still in the area.

Someone should have had enough sense

not to put so many men in the building with this factor still unknown.

However this is all long in the past

and nothing will change history.

I am not ashamed of my conduct and only

wish that I could have done something that would have averted the

disaster.

Surrendering is humiliating.

Being wounded at the time tempers that

reaction somewhat, but not enough to eliminate the feeling. Thus began my saga as a "Kriegsgefangener", the German word for Prisoner of War. |

Thanks to Ken Good for this information and the picture of his father.

|

Sign Guestbook

|